Special Exhibit:

First Signature Series

(Click on any of the images on this page to see a larger version)

This was Doug Spreng’s personal Kraft Signature Series. How important is that? The Signature Series was the premier radio control system of its day—the milestone system which would lead to today’s programmable radios—and Doug Spreng was its designer. But he was much more than that. Doug Spreng made history as a champion RC pilot then he took some electronics courses and changed RC history forever. He invented digital proportional, the modern system of radio control used to this day.

So who else would the best radio control company in the world choose to design the best radio in the world? The choice of Doug Spreng was wise, and the Signature Series earned world-wide acclaim and fame. Its popularity proved so enduring that the Signature Series continued to be produced for many years—even after Phil Kraft and Doug Spreng left the company.

This was the first one ever made—Serial No. 001.

The First Signature Series.

Doug Spreng’s greatest achievement, digital proportional radio control, is recounted below under DIGICON. But our story of this Exhibit begins more than a decade later, at the dawn of a new age in radio control.

Before The Dawn

1974.

It was dark before the dawn.

For years, RC development had been stuck in the rut of routine. The yearly, breath-taking technological advances seemed a thing of the past. The Three Dreams of Radio Control had all been achieved. RC radios had become homogenized, all using the same digital system pioneered by Doug Spreng and Don Mathes in the Digicon (see below).

Talk of circuits and transistors was no longer central at meetings of contest flyers and RC clubs. Reliable radio control was taken for granted. The radio part of the radio control hobby had become boring.

Everything was about to change.

Race To The Top

In late 1974 through early 1975, rumors of Super Radios swirled throughout the RC community. Word was that several manufacturers would soon offer high-end systems beyond anything ever before produced. The rumors were true.

In February, 1975, RC authority Jim Oddino (see S&O One) devoted his monthly RC radio column to speculation about the coming Super Radios (Feb 75 RCM):

No one was sure just how super the new radios would be. Note Oddino’s speculation ranges from spot-on (dual rates, mixing and specialty switches) to far-out (military type force control sticks that don’t move). “At least three” manufacturers were said to be working on these systems.

Behind the scenes it was something like the 1960’s Space Race between the U.S and the USSR. Everyone in the industry knew Kraft was working on its wonder weapon. To be taken seriously, the other RC companies had to have their own Super Radio programs, so they could also claim to be cutting-edge technology leaders. Otherwise they feared their sales of “bread and butter” radios would slip. Thus, Super radios were perceived as a possible money maker in the narrow upper-end niche, and a probable key to future mass market sales and long term viability.

The stakes were high.

Orbit had its top people working almost around the clock on its entry—the Orbit Elite. This feverish pace enabled Orbit to unveil its super system one month before Kraft. The Orbit Elite was rolled out at the March, 1975 WRAM Trade Show and Kraft’s Signature Series at the April, 1975 Toledo Show.

The Orbit Elite had best-in-the-business features like the first ever Liquid Crystal Display, mil-spec components, incredible gimbals and the flashiest exterior ever seen. However, Orbit lacked Kraft’s resources, had fallen far from the days when it led the industry and was secretly on the verge of collapse. To save money, Orbit’s new chief cancelled its engineer’s plans to arm the Elite with dual rates, mixing and other advanced features. This doomed Elite’s competition against the Kraft Super Radio. See Orbit Elite.

E.K. Logictrol engineers were similarly focused on developing their Super Radio. However, like Orbit, they were denied the necessary funding. Consequently, the Championship Series arrived late to the game and ill-equipped to compete with Kraft. See Logictrol One.

Spreng’s Road To Kraft

In fairness to the other manufacturers, competing with Kraft was a tall order. Kraft dominated the industry and could afford to sink large sums into R&D and hire the top talent.

The top talent then was Doug Spreng.

Doug emerged as a leader in radio control in the late 1950s. He won the Nationals in 1960 and again in 1961, rare back-to-back victories. Spreng took some electronics courses but never finished college. RC great Jerry Pullen helped him land an engineer’s position at technology giant Jet Propulsion Laboratories (JPL). In his spare time, Spreng tinkered with RC radios seeking a breakthrough from the myriad problems which had plagued radio control since its inception. In 1962 and 63 Doug Spreng developed the Digicon with Don Mathes—the first commercial digital proportional system. Lacking the funds to continue after problems emerged with initial production units, Spreng returned to JPL. Mathes was hired to run Micro-Avionics, a secret subsidiary of Orbit. Later, Spreng joined him there.

Doug Spreng won third place at the 1967 internationals in Corsica. British contestant Harry Brook proposed a joint venture and Spreng moved to England and developed the Sprengbrook system. He then launched a second system for Stavely tool company.

|  |  |

Then Phil Kraft came knocking.

Spreng missed the California weather, anyway, and Phil Kraft made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. Spreng returned to California in mid-1970 to work at Kraft. Phil Kraft needed help taking his company to the next level after the very successful Gold Medal Series. And, further in the distance, Kraft and Spreng shared a vision of one day making a revolutionary radio dedicated to excellence and unshackled by the budgetary constraints which held all other manufacturers back.

Signature Series

After years of dreaming and months of last-minute preparation, Kraft prepared to introduce the Signature Series to the world at the best possible time and place—the Toledo Trade Show. But first, to pave the way, they distributed a 29 page technical analysis of the historic new system. This was given to RC opinion leaders and VIPs like Walt Good. Here is the introductory page by Phil Kraft (National Model Aviation Museum, Walt Good Collection).

Kraft credits Doug Spreng and describes the overall concept as striving to create the ultimate radio control system without regard to cost. By then, of course, cost considerations had become daily dictators for the design team. But the truth remained that, compared to other systems and other manufacturers, this project truly sought excellence at any cost. Kraft touts this as the “world’s first programmable R/C transmitter.” The owner could mechanically “program” the various settings desired, but this was not done electronically and the Signature Series was not programmable in today’s terms. RC guru Jay Mendoza describes it as user configurable with adjustable presets, but no memory which can be modified, stored and recalled (e.g. for multiple models).

Here is a sampling of pages from the technical analysis (National Model Aviation Museum, Walt Good Collection):

|  |  |  |

|  |  |

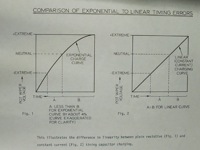

Don’t be misled by the chart on “Exponential.” This discusses the system’s enhanced linearity. “Expo” was an advance which would come later. But what the Signature Series did have was most impressive in 1975. Among the advanced features of this Dream Radio:

--dual rates

--servo reversing

--servo travel adjustment

--push button control of special functions (spin, roll, etc.)

--landing gear positioning

--dual conversion receiver, said to be less likely to drift, swamp or glitch, even near TV or FM stations

--costly, higher quality components; more ICs and fewer separate parts and solder joints to go bad

--the highly regarded Pro-Line gimbals (also used on Kraft’s previous top-end “Z” radios, at least the 2 stick ones)

In addition to all that, each Signature Series would be personally assembled, set up and inspected by the well-known contest pilot and RC authority—Steve Helms. Finally, each purchaser could specify the location of various switches and buttons, to customize his transmitter, and his name was engraved on the front panel. No wonder orders flowed in from around the world.

Production was kept exclusive. Kraft lured the renowned Helms away from Pro-Line to help make this epic program a success. Only Helms and one other engineer were allowed to build the Signature Series, with one exception. The top lady from Kraft’s regular assembly line hand wired the various switches and buttons of each transmitter according to individual diagrams and instructions prepared for each one by Steve Helms. Each time 2 or 3 were near completion, their nameplates would be taken to a local, Vista, California jeweler who would engrave the owner’s name in signature-like script. After Helms left Kraft in 1977, his successors are believed to have employed similar practices.

Such painstaking, labor-intensive production practices assured very few would ever be made. Helms recalls maybe 5-10 systems per week at the peak. Each Signature Series could be unique and they were all prized, limited editions.

Toledo And Beyond

At the Toledo Show unveiling, Steve Helms recalls he and Doug Spreng manned a separate section of the Kraft booth, dedicated to Signature Series. They had a fully functioning example of the system with the servos and receiver on a powered display board so modelers could see the complex, dream radio in action.

In July, 1975, Model Airplane News led its coverage of the Toledo Show with this account of the Signature Series (from the picture do you think the demonstration model was Spreng's?):

One month later Jim Oddino gave this review of the May, 1975 MACS Show in California, where all three Super Radios vied for attention (Aug 75 RCM):

The first advertisement for Signature Series didn’t appear until December, 1975 (Dec 75 MAN):

The system was advertised as a combination of entirely new concepts, custom assembly and a “cost-be damned” approach. The result, a price of $795, is equivalent to over $3,200 in 2010! No surprise ,then, that Signature Series radios were so uncommon and prestigious, and their owners the envy of their clubs.

The reason this first ad appeared so long after the public debut at Toledo is not yet known. One possible explanation is that the system design and/or production was not really ready until near the end of 1975. This often happened with trailblazing new systems. See First Kraft Proportional. However, Steve Helms recalls beginning production 1 or 2 months after Toledo and explains they didn’t need to advertise; the orders came pouring in after Toledo and they quickly found themselves with a backlog.

The earliest regular, dated Signature Series we have is dated November 14, 1975--Serial No. 88. Please let us know if you have an earlier example to shed light on this issue.

The next advertisement for Signature Series appeared in February, 1976 (Feb, 76 MAN):

Doug Spreng's radio may be the very one photographed in this ad. It has the same controls in the same places, along with the obsolete case corner holes(discontinued by Kraft in 1976). Why make an entire John Doe radio configured for no one in particular when they could simply engrave a John Doe nameplate and clip it on someone's existing transmitter?

The transmitter shown in Model Airplane News at the Toledo Show debut also appears to be the same configuration (see picture above). If so, it is even more possible this was Doug Spreng's since it could well have been the only one ready in time. This also helps us date our Exhibit. Since Kraft had no Signature Series ready to display at the March 1975 WRAMS Show, our best guess as to when #001 was made would be late March or early April, 1975.

The transition from the first ad’s hyper detail to this ad’s complete lack of text was classic Kraft behavior. The company was so confident of its reputation, it often felt no need to say anything more than its name in full page advertisements.

Here’s the last 1976 advertisement for Signature Series (Dec 76, RCM):

Sweeping all the top places in a major contest was a favorite promotion for Kraft in earlier years and Pro-Line more recently. Note the lone single stick transmitter. As the years passed single sticks became less common.

A single stick Signature Series cost considerably more than the dual stick version. The one in this ad was Joe Bridi’s. Bridi previously used Jim Oddino’s outstanding S&O radio. In his August, 1975 column above, Oddino acknowledges how Joe Bridi (one of Oddino’s most celebrated customers) would have a much easier time making roll ajustments if only he had a Signature Series. Well, it wasn’t long before he did. Here’s how it looks today:

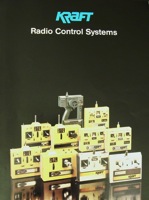

This is how Kraft presented the Signature Series in its 1978 catalog (note the price had been reduced a little). Soon after this the price of a single stick Signature Series rose to $1,000.

The Signature Series was improved over the years with new features like exponential control. It was widely admired and respected and continued in production for many years. In fact, the Signature Series outlasted Phil Kraft, Doug Spreng, Steve Helms and the glory years of Kraft radio control.

As evidenced by this 1982 brochure, the Signature Series was still around after Kraft radios had become a sad shadow of their former glory and the end was coming into view:

Digicon

Being the creator of such a famous, milestone system as the Signature Series was a towering achievement. But it was not Doug Spreng’s greatest accomplishment in RC.

Digicon was.

Digicon enabled Spreng to be considered the father of modern proportional control systems (one of several, to be fair).

Spreng was guided by another “father” of proportional RC, Jerry Pullen. Pullen helped him get a job at Jet Propulsion Laboratories (JPL) where the two had access to the latest transistors and technology. Jerry Pullen demonstrated his pioneering proportional system for Doug Spreng. Spreng was amazed and very impressed with Pullen’s achievement as was everyone else. But Pullen’s system (2+ channels) had limited controls and another basic problem called analog lag. This problem was well explained by RC authority Jack Albrecht in his article on Spreng’s Digicon system (Feb 03’ RCM):

“Jerry’s analog proportional system worked very well and Doug flew one for a while, but it was just too slow to react since it was based on analog tones in the low kilohertz range. The necessary low pass filtering in the tone detection circuits made the response so slow that it interfered with the natural human response time. For instance, you would ask for a little elevator stick control; it doesn’t happen right away so you ask for a little more. By that time the first amount you asked for appears, the little more you asked for when you didn’t see the result of the first bit is just too much. This results in “analog gallop” and it takes all the joy out of flying. Doug just knew the system reaction time had to be less. He figured ten times less would be needed to take human reaction time out of the loop.”

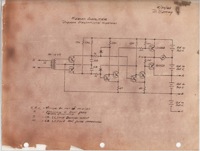

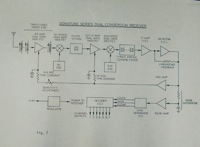

Doug Spreng developed a Pulse Width Tracking system to get rid of the delay. This enabled the response time to be lowered from hundreds to tens of milliseconds. The Bonner Digimite 8 also was digital and used millisecond pulses but the servos were analog so they were still slow to respond. Spreng’s historic breakthrough was to design a new servo amplifier, so the servos could take full advantage of millisecond digital pulses and respond instantly. His design has been used by modern proportional systems to this day. Here is his 1962 schematic for this historic concept; from our encyclopedia of radio control:

By late 1962, the system seemed ready to unveil to the public. Doug Spreng and Don Mathes (who did the RF and mechanical work) formed a company called Digital Control Systems and named their system the “Digicon”. The new product was announced in the December 1962 edition of American Modeler. The receiver was huge, housed in a black plastic case and had no less than six decks. One was the RF receiver the second the logic and the last 4 were servo amplifiers. The amplifiers were built into the receiver to enable use of standard size, light weight servos like the Bonner Duramite and later, Don Steeb servos.

The announcement proved premature. Performance and production problems plagued the new system and it was almost a year before it could be truly introduced to the public. The second new product announcement was in the November/December 1963 issue of American Modeler and the November issue of RCM. A review of the system was presented in the February 1964 issue of RCM:

|  |  |  |

By now the receiver was a more traditional two decks with aluminum case, but it was still huge since it still carried the servo amplifiers onboard. The servos used were now Don Steeb models which RCM couldn’t help but mention were “one of the finest servo units we have seen to date”. The transmitter evolved through three generations (see below) but its exterior always looked like this:

Here are the two generations of receivers and servos:

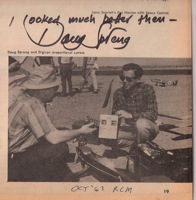

And here is a picture of Doug Spreng promoting the system (October 63” RCM):

Here is the November 63 product announcement in RCM, and the original glossy studio photograph used to make the announcement:

The Digicon was snatched up by top contest flyers like RC legend Jerry Nelson. These were perfectionists, always looking for in edge in the competition. They had to have the very best and didn’t mind paying for it. Putting a new system in the hands of champion pilots was every manufacturer’s dream since contest victories generated great publicity and lead to mass sales. In Digicon’s case this practice quickly killed the company.

At first, flyers couldn’t stop raving about how great the system was, especially the speed and instantaneous response of the servos. But then they discovered that neutrals would drift during flight whenever signal strength weakened (e.g. at distance).

This problem wouldn’t cause crashes it would merely put the ship out of trim from time to time during a flight. To sport flyers the problem would be fairly minor, but for contest pilots it was, and should have been, completely unacceptable. F&M’s Frank Hoover was kind enough to propose a fix in late 1963. By adding his “spike off” scheme the problems disappeared. Spreng and Mathes recalled all existing systems and added the “spike off” for free. This may explain the second new product announcements for Digicon in November 1963.

But it was too late. The damage to their reputation was not so easily repaired and they lost too much time and money in their effort to cure the neutral drift deficiency. Production got further and further behind schedule, orders were revoked and finances crumbled. They now had the world’s best radio control system, fully functional with all the bugs out, but were unable to do anything with it. Fate delivered the Digicon to Bill Cannon.

For the rest of the story, what happened to Digicon after Bill Cannon and C&S took over, see C&S One.

Was Digicon Really First?

Yes.

Digicon is considered the first digital proportional because it was the first “true digital” system to appear commercially. Gordon Larson and Frank Kagele developed the Bonner Digimite and may have had a prototype flying before Digicon’s commercial debut. However, to compare apples-to-apples, we rank systems by first commercialization, usually documented by ads and product announcements and reviews.

Ads, product reviews, brochures and the like are imperfect and sometimes misleading. They are, however, considerably more reliable than alternatives like subjective, often self- serving, fading personal memories and urban myths passed down through the years and “improved” with each telling.

All systems flew earlier in prototype form but information on exactly when, and just how complete and advanced they were at the time, is much less reliable. The Bonner Digimite’s commercial arrival was much later than Digicon’s (partly for Howard Bonner’s strategic and business reasons—see Prototype Bonner Digimite) and Digimite employed an analog servo.

F&M’s Frank Hoover produced one of the first digital systems to hit the market and he helped Doug Spreng remedy Digicon’s initial design flaw. But as advanced as F&M’s proportional was, it definitely reached the market after Digicon.

The Kraft Pullen Proportional had digital electronics and was advertised 1 month before Digicon. However, this was a hybrid digital/analog system, shrouded in mystery and was probably not really finished and available the date first advertised. See First Kraft Proportional.

One of the intriguing issues surrounding the legendary Kraft Pullen is the extent to which the digital portion of its circuits were “borrowed” by Don Mathes from his partner’s work on the Digicon, and whether Spreng may have even been directly involved.

Comparison To Regular Signature Series’

It is informative to compare Doug Spreng’s radio to a regular production Signature Series, such as this early model dated February 13, 1976. Externally, different types or locations of switches and buttons tell us nothing since all Signature Series were customized. Instead of the date under the owner’s name Doug had his HAM operator call sign. The only other difference on the front of the case would be the presence of 4 ”metal bending” holes in the corners. These are seen on Kraft transmitters prior to 1976.

On the bottom, the regular model has a standard Kraft ID plate with the designation KSS-2 and the serial number S-152. Kraft probably used “S” since “SS” had unsavory WWII connotations. Note also the usual “MADE IN U.S.A.” stamped into the vinyl.

Doug Spreng’s radio has none of this, and the serial number is engraved into the vinyl. Under the nameplate, both are the same, including the charging jack "moved" to the bottom on later editions,

Inside, there are a surprising number of differences for a radio which looks so similar on the outside. Spreng’s may have been considered the Mark I model compared to the others’ “KSS-2” designation. The RF section has been altered on our 1976 model so no comparison is made. The encoder board is marked “T-25” instead of “Signature Series”. This may evidence the 25th and final layout or attempt to create a successful Signature Series encoder.

|  |

Other differences include the fourth IC type, doubled resistors behind the ICs, the absence of resistors in several other locations and a few other dissimilar components. The layout of the traces (metal conducting strips, or pathways), on the encoder board is somewhat different, perhaps merely to make room for the “Signature Series” art work on production boards. The traces are also original copper, not tinned or silvered, further evidence that this radio preceded volume production.

Epilog

Doug Spreng disposed of virtually every radio he ever owned including his history-making Digicon. This Signature Series was the exception, which he kept until the very end. He declined all offers over the years to sell it or donate it to a museum.

It was very dear to him and he said he simply could not part with it so long as he lived.

The First Signature Series.